Copernicus died in 1543 in Frombork, Poland, and was buried in the local cathedral. Over the decades, the site of Copernicus’s grave has been lost to history.

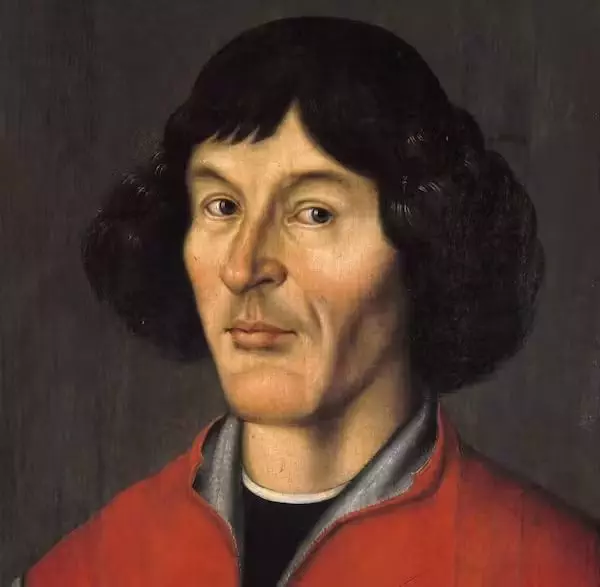

Five centuries ago, scientist Nicholas established that the Earth rotates around the Sun, not vice versa. He was a real Renaissance guy who worked as a mathematician, engineer, novelist, economic theorist, and doctor.

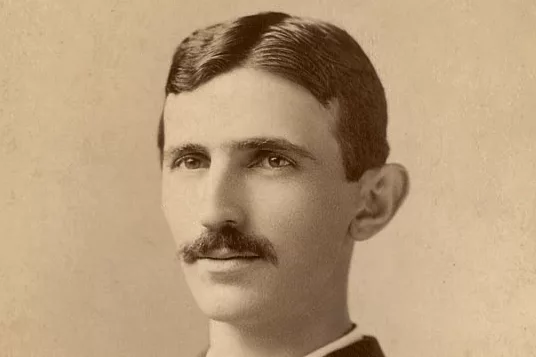

Who was Copernicus?

Nicholas Copernicus (Mikołaj Kopernik in Polish) was born in Toruń in 1473. He was the youngest of four children, born to a local trader.

After his father died, his uncle took up his schooling. Between 1491 and 1494, the young scholar attended the University of Kraków before moving on to Italian universities in Bologna, Padua, and Ferrara.

Copernicus came home in 1503, studying medicine, canon law, mathematical astronomy, and astrology. After that, he worked for his important uncle, Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, the Prince-Bishop of Warmia.

Copernicus worked as a physician while pursuing his mathematical studies. At the time, astronomy and music were both classified as disciplines of mathematics.

During this time, he proposed two key economic ideas. In 1517, he proposed the quantity theory of money. Which was later re-articulated by John Locke and David Hume and popularized by Milton Friedman in the 1960s. Copernicus also developed what is now known as Gresham’s law, a monetary theory governing money’s circulation and price.

The Copernican model of the universe

Copernicus’ groundbreaking concept of the universe served as the foundation for his scientific achievements. Copernicus challenged the prevalent Ptolemaic hypothesis, which held that Earth was the fixed center of the universe, arguing that Earth and other planets orbit around the Sun.

Also, compare the diameters of planetary orbits by expressing them in terms of the distance between the Sun and the Earth.

He was concerned about how his work would be regarded by the church and other intellectuals. His major opus, “De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium” (On the Movement of the Celestial Spheres), was published shortly before he died in 1543.

The publishing of this book laid the groundwork for dramatic changes in our knowledge of the cosmos, opening the way for future astronomers like Galileo, who was born more than 20 years after Copernicus’ death.

The search for Copernicus

More than 100 people are buried at the Frombork Cathedral, with the majority of them in unidentified graves.

There have been countless fruitless attempts to locate Copernicus’ bones, dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries. Following the Battle of Eylau in 1807, French Emperor Napoleon attempted another fruitless assault. Napoleon admired Copernicus as a polymath, mathematician, and astronomer.

In 2005, a group of Polish archaeologists began the quest.

They were prompted by historian Jerzy Sikorski’s idea. Which said that Copernicus, as Canon of Frombork Cathedral, would have been buried near the cathedral altar. For which he was responsible throughout his tenure. This was the Altar of Saint Wacław, currently called the Altar of the Holy Cross.

Furthermore, thirteen bones were unearthed around this shrine, including a fragmentary skeleton of a guy aged 60 to 70 years. This skeleton was found to be the most similar to that of Copernicus.

Forensic science

Moreover, the skull of the skeleton served as the foundation for a face reconstruction.

In addition to morphological investigations, DNA analysis is frequently employed to identify historical or archaeological remains. The well-preserved state of Copernicus’ teeth made genetic identification possible.

Finding an appropriate source of reference material was a considerable difficulty. There were no known remnants of Copernicus’ family.

An unlikely find

In 2006, however, a fresh source of DNA reference material emerged. An astronomical reference book used by Copernicus for many years was discovered to have hair on its pages.

This book was brought to Sweden as war loot after the Swedish conquest of Poland in the mid-seventeenth century. It is presently in the hands of Uppsala University’s Gustavianum Museum.

A thorough analysis of the book discovered numerous hairs, most likely belonging to the book’s initial user, Copernicus himself. As a result, these hairs were considered prospective reference material for genetic comparison with the teeth and bone materials discovered in the tomb.

The hairs were matched to the DNA found in the teeth and bones of the recovered skeleton. The mitochondrial DNA from the teeth and the skeleton sample matched those from the hairs, indicating that the remains were undoubtedly those of Nicholas Copernicus. The comprehensive endeavor, which included archaeological excavation, morphological investigations, and sophisticated DNA analysis, resulted in a strong conclusion.

The bones recovered near the Altar of the Holy Cross in Frombork Cathedral are most likely those of Nicholas Copernicus. This remarkable discovery not only reveals the last resting location of one of science’s most influential thinkers but also demonstrates the breadth and sophistication of current scientific procedures for corroboration of historical evidence.